We often only think about markets regarding risk and return, where risk is measured by the standard deviation of returns. It is easy to calculate and update. Unfortunately, the changing nature of markets makes for messy calculations and analysis. Assuming a normal distribution is just too simple for measuring risk. Instead, investors have to be aware of skew in return distributions. More specifically, investors have to account for negative skew because the unexpected extra downside risk is what hurts portfolio returns.

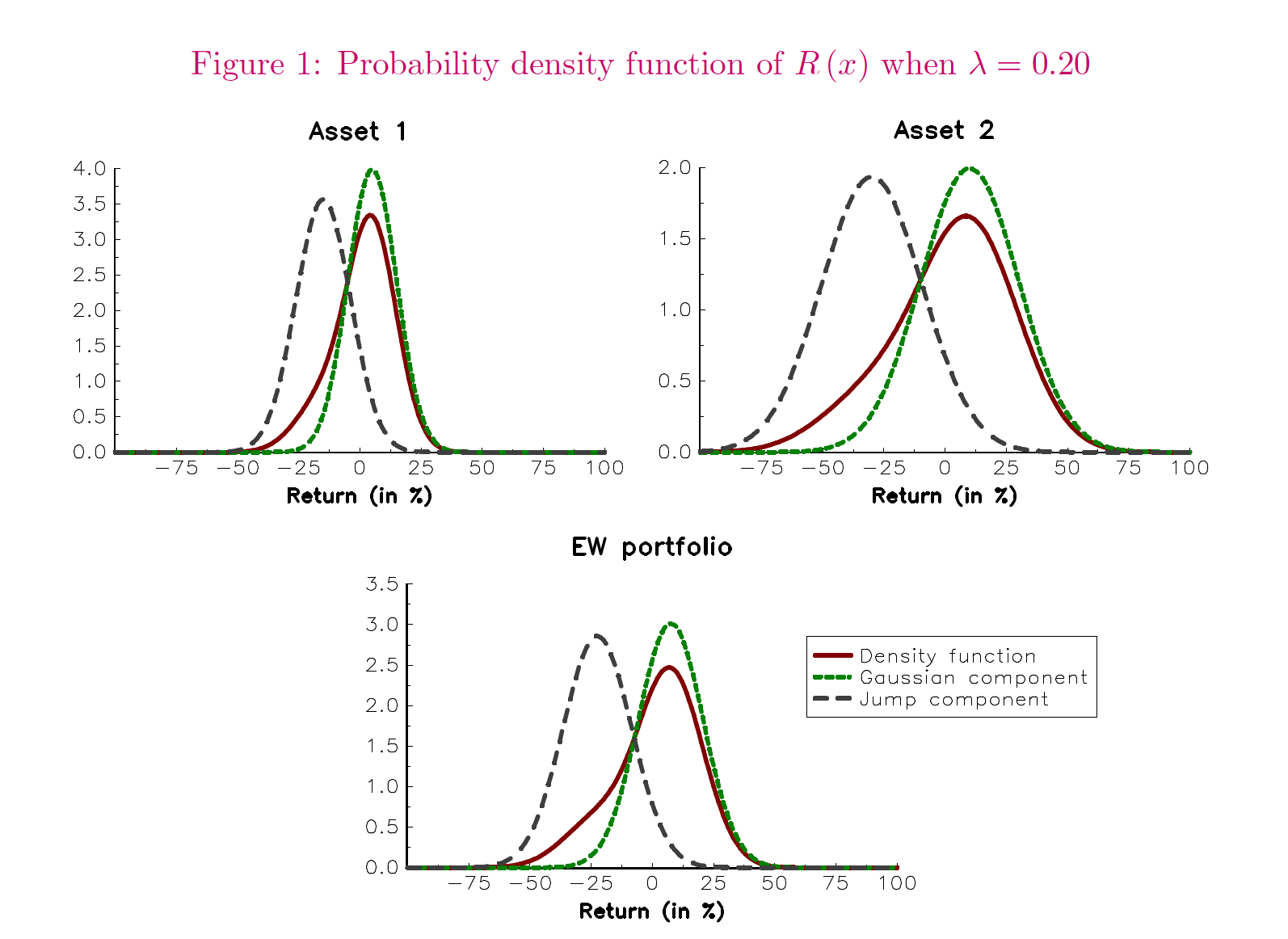

Skew can be explained or modeled through a mixed distribution approach. But, if you have normal price dynamics mixed with a jump process for some negative shock, you will get negative skew in the mix. You can think of jumps as regime shifts with a low probability of occurring.

All an investor has to do is look at the shock behavior of markets from financial crises or recessions to see that a mixed distribution is relevant. Jumps can be predicted to occur, but that does not mean we know when they will happen. Interestingly, the impact of jumps and, thus, negative skew becomes more relevant when normal volatility is low. Conversely, high volatility will mask the jump impact, so the skew risk is more significant when markets seem calm.

The impact of skew can be incorporated in a risk parity portfolio approach with meaningful results. If a Gaussian mixed distribution is used to proxy for skew, risks can be balanced beyond just volatility. Suppose there is more skew within the assets to be allocated. In that case, there will be more significant adjustments in portfolio allocations relative to the conventional risk parity approach or just mean/variance optimization.

New research by some leading advocates of risk parity shows that accounting for skew is relevant. The adjustments in allocations are meaningful and can help offset the risks from jumps in return behavior. See “Risk Parity Portfolios with Skewness Risk: An Application to Factor Investing and alternative Risk Premia.” Volatility management in a risk parity framework will create more turnover and only capture events after the fact. Accounting for skew can reduce turnover and account for jumps before they occur. For example, if there is a negative jump or shock, volatility will rise after the event causing a decline in allocation to this risky asset. Unfortunately, this is too late. Accounting for skew from the chance of jumps would have forced a lower allocation to the risky asset and better addressed the potential for a negative shock.

Since not all strategies or asset class behavior have the same skewness or response to jumps, strategies, risk premiums, and price behavior must be carefully analyzed. Some risk factors are more subject to jumps, so accounting for skew is more important. Skew should be measured, but more importantly, it can be contained separately from volatility.

Photo by Daniel Falcão on Unsplash