Category: Uncategorized

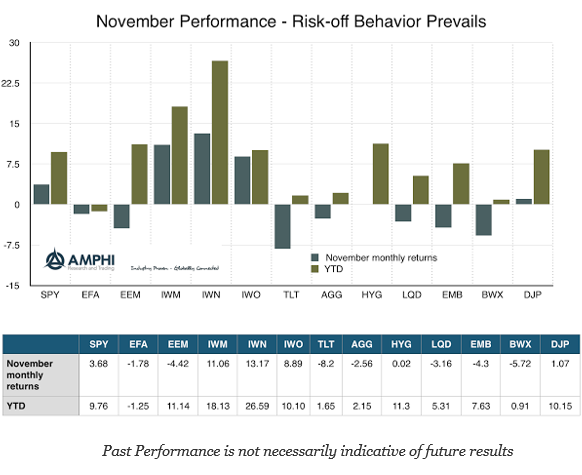

The Big Bond Break and Equity Revival – November Performance

For those who had a “safe” portfolio skewed to bonds before the election, it was a disaster month. For those who were stock-pickers in value and small cap, it was a dream market. The return differential between bonds (TLT) and value (IWN) was more than 20% in one month. Call it a “Trump Rally / Trump Bond Sell-off”, but the financial world changed beyond politics. This sound bite story may be getting old, but there is a lot going on in markets beyond being long stocks and short bonds.

Data Mining – More than Collecting Data Ore

There are fads and fashions in finance and business. Some statistical techniques come and go in and out of favor based on expectations of success and the realization that some tools just cannot solve certain problems. Data mining in now a hot topic in many areas of business, yet there are not clear definitions of what data mining means, what tools it represents, and how it can solve problems. Clearly, the low cost of computing and storage has made the collection of data much easier, but the problem is not with the data. The issue is how you extract the data “ore”, how it is processed, and what you do with it once it is modeled.

Due Diligence of Trading Skill – Can it be Improved?

Being on both side of the table concerning the due diligence of managers, I can argue that there has been a significant improvement with the skill at conducting operational due diligence. Operational risks can be effectively identified and measured. There will be fund failures, but investors can do a good reasonable job of handicapping firm-specific risk. There are checklist and processes that can support the choice of managers. The operational due diligence has been effectively institutionalized.

Brains and Stomach – You Need Both for Investing

Having the stomach for investing means that you are able to get over the behavioral biases that are based on emotions and fast thinking. It means being able to follow-through with an investment plan without emotions. Meir Statman, a finance professor who has focused on behavioral biases, states, “Deeply buried fears can keep us from taking risk – keeping us safe, perhaps but also robbing us of potential returns. A stronger tendency to regret past choices can keep us from repeating blunders, but also from repeating sound strategies that simply didn’t work out the first time.” from Spencer Jakab, Heads I Win, Tails I Win. Those who have regret have no stomach. Investors who can move beyond regret have the stomach for investing.

Investment Learning Starts with Knowing the Past

I have always had problem with some of the finding behavior finance research. The research is good at pointing out flaws but less effective at offering ways to improve performance and behavior other than stop doing bad things. Nevertheless, I have found some the behavioral research work by Markus Glaser and Martin Weber very helpful with how to offset some biases. They find that there is no correlation between return estimates and realized returns, but they see difference in behavior based on experience. See their work, “Why inexperienced Investors Do Not Learn: They Do Not Know Their Past Portfolio Performance”.

Arbitrage and Ethics – Food for Thought

I don’t think many finance professionals would link arbitrage and ethics together. There is an ethical link between being a fiduciary and handling money for clients. Trade organizations and MBA schools will tie business practices, ethics, and being a fiduciary, but you would not expect discussion of ethics matched with talks on arbitrage, but Maureen O’Hara, a esteemed professor of finance at Cornell University has done just that with her new book Something for Nothing: Arbitrage and Ethics on Wall Street.

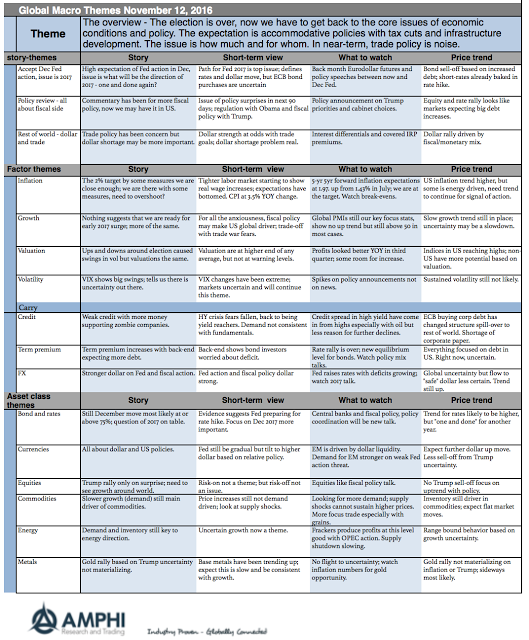

Global Themes on One Page

We have delayed our monthly global themes on one page given the US presidential election. There was too much uncertainty associated with the election to focus on the core themes of growth and valuation. Now that the election is over, we can focus on what is most important, growth, liquidity, and risk appetite. Financial markets are driven by the underlying economics of policies and not the personality of the president. Focus on policy, not the man. Personality matters to the degree that policy agendas can be moved. This is not trivial, but what moves markets are the policies. The key is determining what will get done, when, and how much. These policies have to be balanced with growth prospects around the world.

Liquidity Premium – Not Easy to Sort-Out

There is a strong demand for liquidity in all investments even hedge funds. However, there is a difference in the liquidity across hedge fund styles. The key investment question is whether you get paid to hold less liquidity. Is there an illiquidity premium?

Sector Exposures

October was a painful month for investors with no place to hide in many sectors, styles, countries, or bonds. Major equity styles declined significantly especially in small caps.

Quantitative Analysis

A provocative post by Peter Lupoff the founder of Tiburon Capital called “When numbers cloud meaning – The fallacy of investment research exactitude” has me thinking about narrative versus the idea of false precision with quantitative analysis. First, something to put the issue into context; a classic joke on false precision, “I am 98.54% certain that you need both precision and narrative to be an effective trader.”

Crunch Time in Bond Markets Makes Equities More Vulnerable

Since the post Brexit plunge in bond yields, we have been becoming more negative on bonds. Along with virtually everyone, except central bankers, we have been banging the drum of how insane negative bond yields are. However, with many institutional investors required to hold Government bonds due to regulatory and capital requirements, and central bank’s QE exceeding global Government bond supply, it was almost understandable how bond yields could remain in sub-zero terrain. Understandable yes, but that did not make them good investments!

Cognitive Biases

The list of cognitive biases that can affect investors keeps growing. An explosion of studies show that observed decision-making under real and test conditions is hard. Just look at the wheel from Buster Bensen’s cognitive bias cheat sheet, the single best graphic I have seen which lists and categorizes the cognitive biases investors face, to get a flavor of the problem. Nevertheless, this work does a good job of reducing all of these biases into four problem categories:

Can The World Cope With a Resurgent Dollar?

There is no doubt that big swings in the value of the US Dollar have a big impact on global economic growth and also financial markets performances. Between June 2014 and January 2016, as the Dollar rose by over 20%, global equity markets struggled (Emerging Markets suffering the most), commodity prices plunged and deflationary concerns moved front and center. After the Dollar topped in late January, everything has turned around. The Dollar has traded sideways, financial markets have performed pretty well overall and economic concerns have abated. Although it cannot all be about the Dollar, we need to recognize that the Dollar is extremely important for both financial markets and the global economy.