Archives

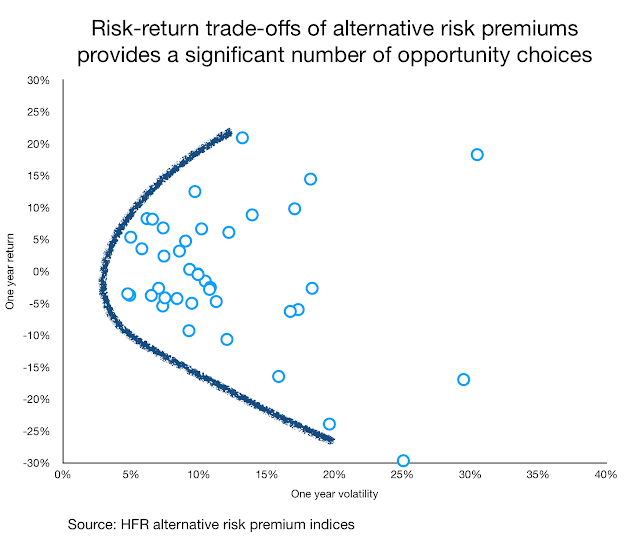

Alternative Risk Premium Indices – Providing insight on what is possible in the ARP space

HFR, the hedge fund index provider, announced a new set of indices based on alternative risk premium strategies generated from banks. This is a major advancement in transparency for investors and shows the strength in this growing sector of investing.

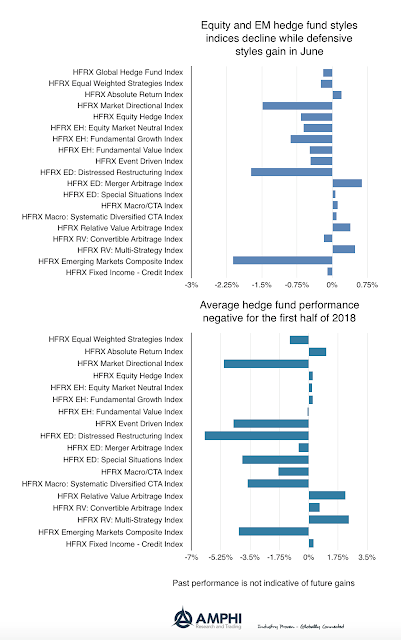

Hedge Fund Performance Poor for 2018 – Limited Alpha Generation

Hedge fund styles as measured by the HFR indices, on average showed negative performance for June. EM strategies were the hardest hit sector. The only bright spots were merger arbitrage, defensive strategies like global macro and relative value. The general decline in equity markets globally and more mixed performance in the US held back returns.

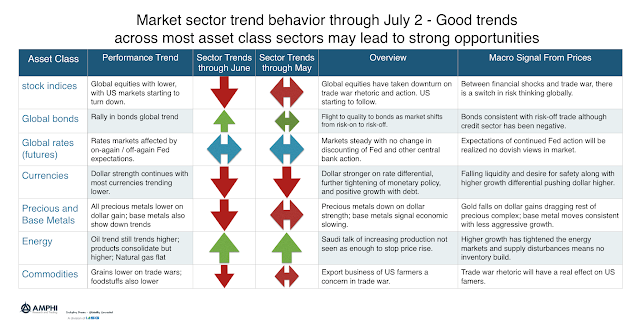

Strong Trends Across Most Asset Class Sectors Point to a Strong Opportunity Month

A review of trends in each of the major asset class sectors shows that there should be a strong return opportunities in July. Global stock indices are declining on trade war rhetoric and action. This growing sense of risk has spilled-over to bond markets through classic risk-on/risk-off behavior. Bonds have gained even with the threat of higher inflation. The dollar looks to continue its up trend as money flows back to the US and away from EM. Precious metal prices have fallen on the dollar strength. In spite of the Saudi’s willing to increase oil production in response to falling inventory, oil prices have continued to trend higher. Grain prices have fallen on fears of a trade war in agricultural exports to China. The general direction in commodity prices has been lower.

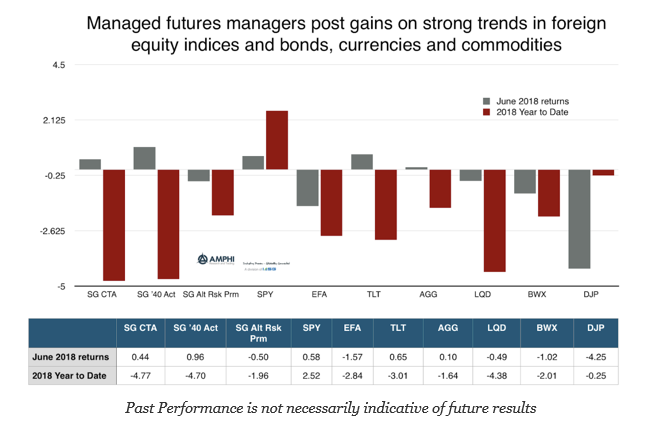

Managed Futures Show Gains versus Other Asset Classes Based on Good Trends

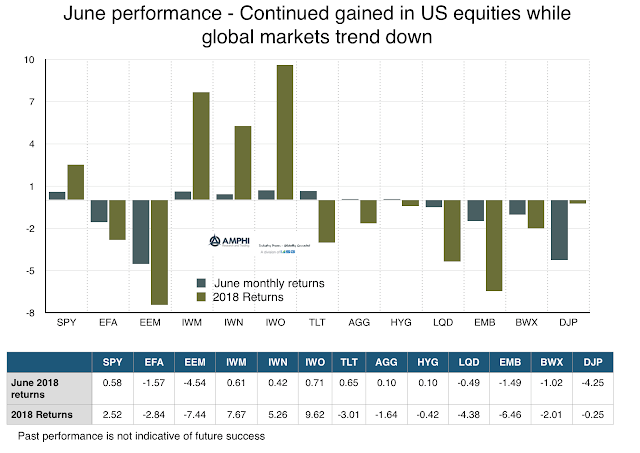

Based on the performance of the SocGen indices, the average managed futures fund generated positive returns for June. The performance of the Barclays BTOP also was up 59 bps and is only down three percent for the year. Managed futures outperformed all of the major asset class ETFs based on strong trends across a number of asset classes.

Hotter Financial Markets Will Match Summer Heat – But That May Not Be a Positive

There is a US/Global equity market disconnect. The higher US growth, optimism, and fiscal stimulus (tax and debt financing) have created a positive economic environment for the US that is not seen in the more lethargic global economy. US growth is expected to surge above 4% for the second quarter (per the Atlanta Fed nowcast) even with slight downward revisions for the first quarter. Global growth is not bad and is expected to exceed 2017, but economic shocks in the EU and EM and tightening China liquidity have all contributed to more fragile global stock markets. China equities, at least measured from the high, are in a bear market.

Downside Risks Abound – Beware of Summer Heat for International Investments

There is a large disconnect between US equities and global equities. The US equity markets seem out of touch with the financial difficulties seen in other parts of the globe, albeit recent price action suggests downside risks increasing. The gap between the small cap and emerging market indices is now above 15% for the first half of the year. Still, there are signs that the disconnect will not last as most styles have fallen below short-term (20-day) moving averages.

Risk Should Not Be Determined by Feelings of a Past Experience – Block the Perceptions and Focus on Some Numbers

Risk perception is often about pain and not probabilities. It is about the experience of risk not the mathematical chance or size of loss. I would like to say that everything about risk management is measurable and can be reviewed dispassionately, but that is not the case. There is often a difference between fear and facts and this is the perception gap which often leads to bad judgment. You may be a dispassionate risk assessor, but the market’s perception of risk may be driven by its weighted perception of the risk.

The Power Law, 80/20 Rule, and Concentration of Returns – What It Means for Money Managers

The power law has been become a strong fascination to me. We have been trained to generally think about the normal distribution. The law of large numbers has been pounded into our psyche since our first class in statistics but as you look more closely, the more relevant the power law becomes. Now, a normal distribution will produce extreme values. However, in a power law the extremes follow certain characteristics such that the “top few” are unbundled or more likely to have an extreme, (as opposed to a normal distribution where the “top few” are exponential and bounded).

Ride the Trend, but Remember What Is Possible

“I am not an optimist. I am a very serious possibilist.” – late statistician Hans Rosling.

“I am a trend-follower for both price and fundamentals. I am also a very serious scenario realist.”

How do investors reconcile potential storm clouds with optimistic trends in markets. There is ongoing information of long-term economic problems from a wide variety of sources today, yet many markets have continued to move higher and followed trends. There often seems to be disconnects between long-term peril or risks and shorter-term optimism. Some says this is the essence of a bubble market, a disconnect between price and fundamentals, yet avoiding trends based on yet to be realized threats can easily cause investors to avoid profitable opportunities.

Active Management Should Work Because Active Managers Work Hard – You Are Committing a Fallacy

Which is more likely? A manager who has successful returns, or a manager who has successful returns and gets up early, works hard all day, and spends half the night reading current research. Which one will you choose to run your money?

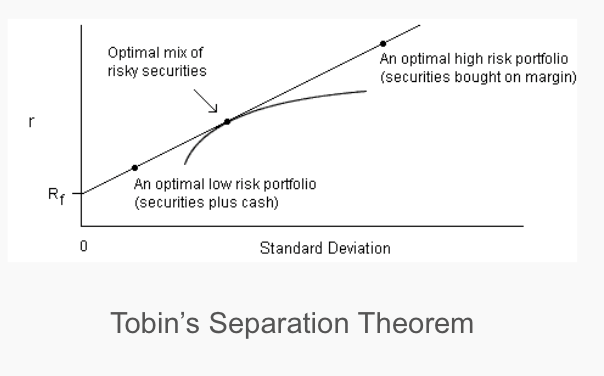

Tobin’s Separation Theorem – It Can Be Applied Anywhere

One of the greater principles of investment finance is Tobin’s separation theorem which is a powerful simple tool that can be used for any investment portfolio, but is especially useful when thinking about managed futures and alternative risk premiums. (Robin Powell reminded me of Tobin’s contribution in his essay, Can you really stomach the risk you’re taking?) There is a tremendous amount of useful investment advice through just applying the simplest of concepts.

Commodity Returns Over the Long-Run – A Good Diversifier, So Get Back in with an Asset Allocation

Commodity index investing has not been very successful for investors as measured by leading index total returns since the Great Financial Crisis. The end of the super-cycle has been tough on most investors and only recently has there been a period of extended positive returns based on the rise in oil prices. Is there any relief for investors?

Decision Noise Reduction – This is the One Thing Investment Managers Should Get Right

“There’s a lot of noise when making a decision. Not in the decision itself, but in the making of the decision. It is possible that an algorithm, and even an unsophisticated algorithm, will do better because the main characteristic of algorithms is they’re noise-free. You give them the same problem twice, you get the same result. People don’t.”

– Daniel Kahneman keynote at the Morningstar Investment Conference in Chicago 2018